Edward Mezvinsky

Link to text version of timeline

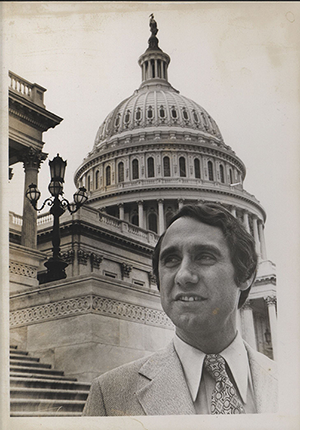

When Mezvinsky arrived in Washington, D.C. in January of 1973 as part of the 93rd United States Congress, the events of the Watergate break-in and President Nixon’s troubles with the ITT scandal seemed to have been largely ignored by the American people. Nixon had, after all, just won a landslide election against his Democratic opponent, and as President, appeared to have a mandate to enact his policies, both in Vietnam and domestically.2 Just a week into Congress opening its session, the trial of the five Watergate burglars began and the scandal once again entered into the public eye. By the end of January, two of the burglars had pleaded guilty and were convicted of crimes relating to the break-in. By the middle of March, 1973 one of the two convicted defendants, James McCord, wrote a letter to the Chief Judge of the District Court of the District of Columbia claiming that he was pressured to plead guilty and to remain silent about the break-in. The letter insinuated that high ranking officials in the Nixon administration were orchestrating a cover-up of the Watergate break-in.

The Watergate trial and subsequent letter by McCord enflamed the scandal, as politicians began to reexamine the Nixon administration’s role in the affair and what they viewed as misuses of power. At the forefront of the renewed interest was an “informal caucus” of thirty newly elected Democrats from the House of Representatives, chaired by Edward Mezvinsky.3 In a New York Times article, Mezvinsky stated that the caucus wanted to “act as a catalyst” in getting Congress to confront the Nixon White House, pointing to both Watergate and to Nixon’s refusal to send witnesses and advisors to answer Congressional questions regarding everything from the break-in to budget issues.4 Another influential member of the new caucus was Barbara Jordan, a fellow first term Democrat from Texas who was also only the second African American elected to Congress since the end of Reconstruction. In a discussion of how the caucus viewed its role within Congress, Mezvinsky told the New York Times that “all of us came out of the grassroots, where we found a strong feeling that Congress should be a dynamic branch.5 Not long after forming, the new caucus would flex its newfound muscle by pressuring Speaker of the House Carl Albert into letting the new Democratic House members take control of the House floor for approximately four hours, where they aired grievances against the Nixon White House over Vietnam, Watergate, and proposed budget cuts. According to a New York Times piece, the first term Democrats were among the first politicians to openly discuss impeachment, a full year before actual impeachment proceedings would occur.6 Perhaps representative of a clash between generations, Ray Madden, an eighty-one year old Democrat from Indiana reportedly said after hearing of the impeachment talk, “It’s a hell of a thing when you hear about impeaching a President.” 7

As the Watergate scandal continued to grow through 1973, Mezvinsky and other politicians began to feel displeasure among the American people. “Since the election,” Mezvinsky told the New York Times, “I think the disillusionment with the government has grown rather than diminished.” 9 Following months of Senate Watergate hearings, discoveries that Nixon had secretly recorded conversations in the White House, and the infamous Saturday Night Massacre, which saw the U.S. Attorney General and Deputy Attorney General resign after refusing to fire the special prosecutor charged with investigating the Watergate scandal, distrust for government was growing among American voters. In January of 1974 during a trip back to Iowa’s 1st District, Mezvisnky heard firsthand the anger of voters from the Midwest. In a public meeting in Burlington, several voters attempted to link Nixon’s Watergate scandal with rising oil costs, as they called the energy crisis a “hoax” and a “rip-off” so that oil companies could make more profit.10 According to a letter from a Burlington widow, “I don’t trust our government anymore or big businesses.” 11

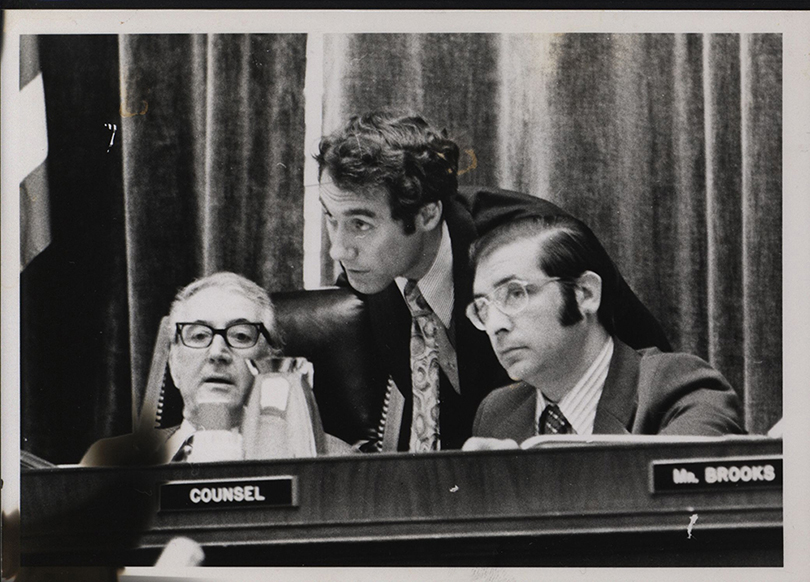

In addition to chairing the informal caucus of first term House Democrats, Mezvisnky also held a seat on the House Committee on the Judiciary. If impeachment were to become a reality, it would be the Judiciary Committee that would make the determination on whether to present articles of impeachment to the full House of Representatives. By May of 1974, Mezvinsky and his fellow committee members were, indeed, tasked with beginning impeachment proceedings against President Nixon.13 Throughout the summer of 1974, the Judiciary Committee met to discuss whether Nixon’s conduct rose to high crime or misdemeanor. Beginning on July 27, the committee began four days of voting on five articles of impeachment drawn against President Nixon. The articles concerned obstruction of justice, abuse of power, contempt of Congress, bombing of Cambodia, and failure to pay taxes. Mezvinsky supported the articles of impeachment, including the one he drafted and sponsored relating to Nixon's income taxes and personal finances.14 The first of the three articles passed the committee, while the last two failed to receive enough votes. By July 30th, 1974 with three articles of impeachment approved by the Judiciary Committee, the House of Representatives could bring formal impeachment to the full chamber. The House, however, never voted on impeachment. Richard Nixon resigned from office on August 8th, 1974.

While his association with Nixon’s impeachment proceedings was understandably a historically significant event, Mezvinsky was active in Congress well beyond the confines of his seat on the Judiciary Committee. During his two Congressional terms, Mezvinsky sponsored or co-sponsored several pieces of legislation, including a resolution to require Congressional authority to re-involve American forces in Indochina, a pro-environmental amendment to a resolution to better regulate strip mining in Appalachia, and a resolution to express Congressional disapproval towards an effort to expel Israel from the United Nations.15 After Nixon’s resignation, and with Watergate behind him, Mezvinsky took an interest in foreign policy concerns, especially on issues relating to Israel and the evacuation of refugees from South Vietnam.16 One of Mezvinsky’s last pieces of legislation in 1975 allowed for the immigration of Southeast Asian child refugees into the United States.17

In the 1976 Iowa 1st District race, Mezvinsky faced Republican James Leach. During the campaign, Leach argued that Mezvinsky, due to his work on Watergate and his advocacy for Southeast Asian refugees, was no longer representing the local interests of the 1st district. By a margin of roughly nine thousand votes, the Republican challenger unseated Mezvinsky. 18

- 1. Photograph from Box 19, Folder 1, Edward M. Mezvinsky Papers, MS 274, Iowa State University Library Special Collections and University Archives.

- 2. The Pentagon Papers, leaked by Daniel Ellsberg and published in The New York Times (beginning in June of 1971) largely failed to erode the support of the American voters for Nixon’s Vietnam policy.

- 3. The New York Times, 12 April 1973.

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. Ibid.

- 6. Speaker Albert, perhaps in an attempt towards solidarity with his new representatives or reflective of his own frustration with the Nixon administration and House Republicans, joined the caucus on the House floor. The New York Times, 24 April 1973.

- 7. Ibid.

- 8. Box 10, Folder 13, Edward M. Mezvinsky papers, Iowa State University Library Special Collections and University Archives.

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. New York Times, 15 January 1974.

- 11. Ibid.

- 12. Photograph from Box 19, Folder 4, Edward M. Mezvinsky Papers, MS 274, Iowa State University Library Special Collections and University Archives.

- 13. Barbara Jordan was also a member of the Judiciary Committee. Her speech before the committee on the significance of what they were about to do has become a classic text in American political history. Two days prior on July 25th, Barbara Jordan delivered her famous televised speech before the committee regarding the impeachment process. An audio recording of Jordan's speech is available online at https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/barbarajordanjudiciarystatement.htm

- 14. Biographical Note, Finding Aid to the Edward M. Mezvinsky papers, Iowa State University Library Special Collections and University Archives. http://findingaids.lib.iastate.edu/spcl/manuscripts/MS274.html.

- 15. Box 13, Folder 4, Edward M. Mezvinsky papers, Iowa State University Library Special Collections and University Archives.

- 16. Mezvinsky, A Term to Remember, 248.

- 17. Mezvinsky, Edward, interview with Mark Barron and Hilary Seo, 8 October 2018. Parks Library, Iowa State University.

- 18. The Sumner Gazette, 11 November 1976 and The Carroll Daily Times Herald, 6 December 1976; Mezvinsky, Edward, interview with Mark Barron and Hilary Seo, 8 October 2018. Parks Library, Iowa State University.

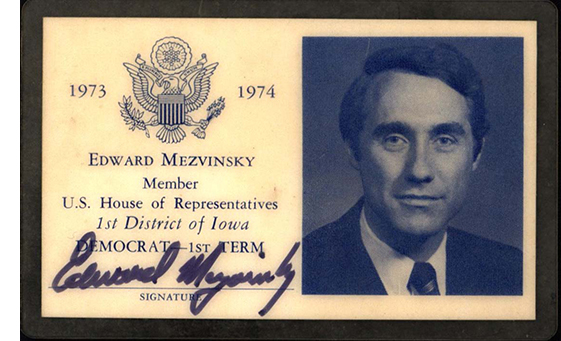

- 19. Artifact 2009-008.001, Edward M. Mezvinsky Papers, MS 274, Iowa State University Library Special Collections and University Archives.