We Are ISU: Snapshots of Student Life

Seasons of Change (1959-1988)

Following national trends, ISU students of the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s began to push back against previously-unchallenged cultural norms. Students of the era would have witnessed, if not participated in, numerous protests and public conversations favoring women’s rights, LGBTQIA+ rights, anti-Vietnam-War sentiments, and many other issues during their time on campus. A unified effort on behalf of black students, alumni, and staff – largely unaided, frequently ignored, and occasionally even hindered, by ISU administration until very late in the game – also established the Black Student Organization, the Black Cultural Center, and eventually the Office of Minority Student Affairs (currently Multicultural Student Affairs). The success of these organizations in turn inspired a crop of multicultural student organizations during the 1980s and initiated a number of critical conversations that are ongoing today.

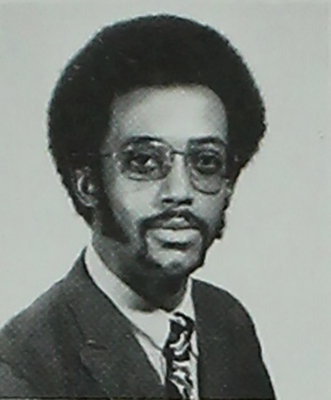

Student Spotlights: Vern (M.S. 1976, B.S. 1972) and DeLores Hawkins (M.S. 1984, B.S. 1973)

Vernie Hawkins and DeLores (née Williams) Hawkins completed their undergraduate degrees against the backdrop of several pivotal points in history, on a national level and at ISU. Vern, an English major from Des Moines, and DeLores, a Journalism major from Chicago, were both actively involved in the formation of the Black Cultural Center, first as students and then later as ISU staff. Although Vern had initially been denied entrance to ISU, ostensibly because his grades from community college (which he attended at night while helping to support a sister and single mother) were not high enough, he eventually received the coveted Cardinal Key honor in his senior year, and both he and DeLores went on to complete their masters degrees while employed at ISU. The couple still resides in the area.

Snapshot of Campus in 1973:

- President: William Robert Parks

- Student Population: 19,267

- New Campus Buildings: Bessey Hall (1967), Zaffarano Physics Addition (1968), Carver Hall (1969), Town Engineering Building (1971), Science Hall II (1972), Ross Hall (1973)

Student Life

Residence Hall

Finding housing had been a major hurdle for African-American students since the beginning of the university, as unofficial (but nevertheless enforced) policies had long prevented them from lodging with fellow white students. DeLores, one of only a handful of (non-international) black women studying at ISU at the time, initially lived with faculty and administration staff1. Vern, on the other hand, lived in the Dodds House (1972 Bomb, page 177).

Academics

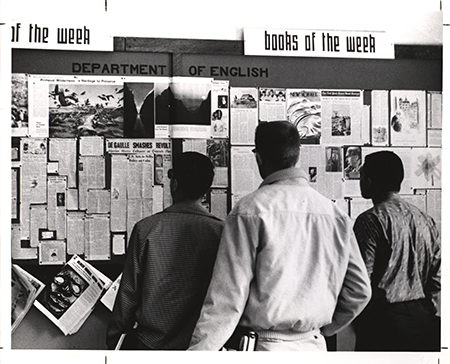

The chair of the English department during Vern's undergraduate years was Albert L. Walker, who, beyond his generalist expertise in English literature2, held a particular passion for Southwestern Native American art and culture, which he researched with the aid of his wife, Jauvanta M. Walker3. While the English department and all within it were considered a part of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the Department of Journalism and Mass Communication (so named in 1969, the year DeLores arrived on campus), was not. Until the 1990s, Journalism was part of the College of Agriculture4.

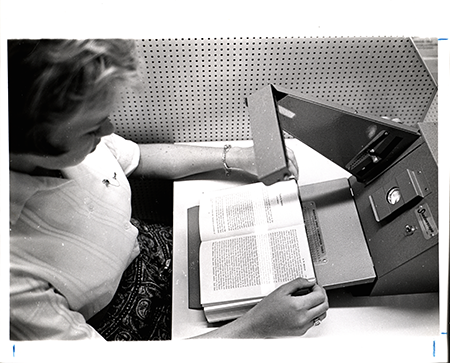

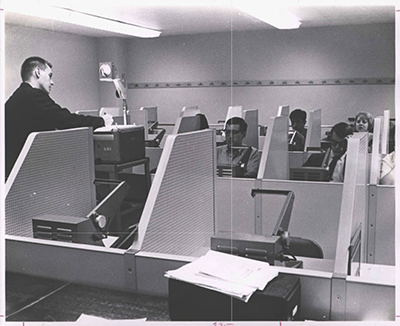

Classroom Technology: Reading Machines

ISU has been known for its technical innovation in all areas of study, and the humanities have been no exception. While they seem to have gone out of style within the decade, so-called “reading machines” assisted English majors and remedial freshmen of the 1960s with developing their speed-reading skills. A light would scan down the page of a book at a pre-selected speed and help improve concentration. As the second picture shows, machines were stationed in individual carrels but seem to have been used in a classroom environment, rather than for individual study.

ISU Experience: The Monopoly Edition

Regardless of the political turbulence of the time, students of the early 1970s shared many of the same day-to-day joys and concerns that crop up in the lives of students today. The 1971 yearbook immortalized these quintessential patterns of ISU student life in the form of a Monopoly-inspired board game. Students could simply open their yearbooks to the right page and play a round with friends using coins or paperclips as game pieces (1971 Bomb, pgs. 88-89).

The Black Cultural Center

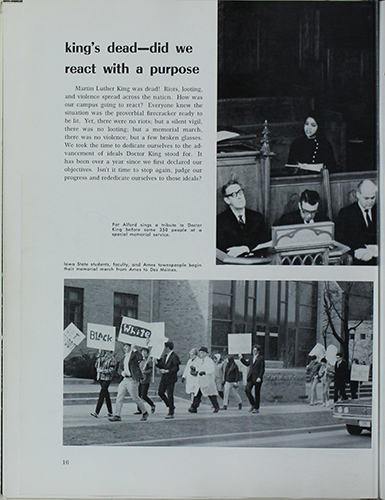

Students Respond to MLK Assassination

News of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death on Wednesday, April 4, 1968 – Vern's second semester at ISU, and mere months before DeLores arrived on campus for her freshman year – created an urgent sense amongst ISU’s black students to address a need for more unity, visibility, and support.

The next evening, Thursday, April 5, black students met to form a group they provisionally named the “Afro-American Students of Iowa State University,” identifying fellow students Bruce Ellis and Louis Lovelace as their leaders. Then, on Friday, April 6, approximately 50 demonstrators assembled in Memorial Union, toasted to “black unity on campus,” then quietly tossed away their cups, overturned the tables and chairs, and left. Ellis issued the statement to the Iowa State Dailyexplaining the purpose of the protest: “We, the Black Students of Iowa State University, are here to awaken YOU to the conditions and consequences of the situation which has led to the violent death of our non-violent leader, the Most Reverent Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.”5

Within weeks, the student group had translated their purpose into a constitution, which they signed April 23, 1968. From that point on, they were known as the Black Student Organization (BSO) (1969 Bomb, pg. 16).

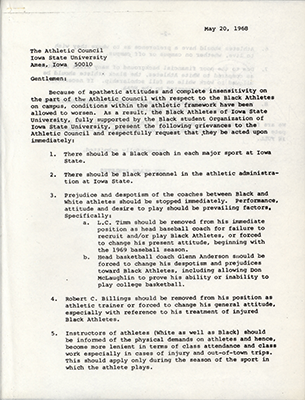

The "Eight Grievances"

On May 20, 1968, the newly-formed Black Student Organization took their campaign for equitable treatment to the administration in the form of a letter which would come to be known as the “Eight Grievances.” The letter presented a list of terms, mainly centered around the concerns of athletes, and petitioners threatened to leave ISU if the administration did not act on them. Unfortunately, the administration rebuffed several requests related to representation. The administration’s response invoked an allegiance to colorblindness in their hiring practices, and at least two student athletes made good on their promise to leave the school as a result of the lack of cooperation. The full paper trail of their exchange can be viewed in the archives.

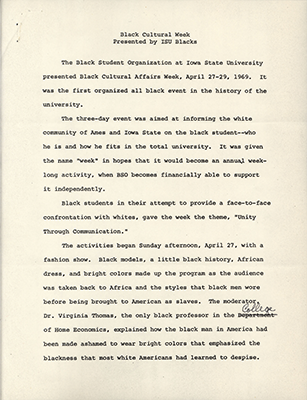

Black Cultural Week

It is unclear whether this "first annual" Black Cultural Week, held a year later on April 27-29, 1969, was ever repeated, or when it was discontinued and why. That said, this descriptive report shows that the Black Student Organization followed-through on their early intentions to promote cultural awareness to the campus at large as well as their impetus towards unified action that would establish the Black Cultural Center the following year.

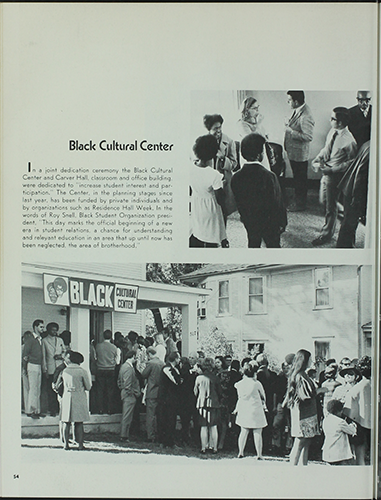

Dedication of the Black Cultural Center

The Black Cultural Center was officially dedicated on Sunday, September 27, 1970, following the long process of searching for and acquiring a location. The process had been waylaid by the university's refusal to offer funding towards the purchase of the center (though President Parks did publish information encouraging faculty and other community members to donate privately to the cause). However, students, alumni, and community members pulled through, pooling resources that would enable them to purchase the $30,000 property at 517 Welch Avenue (1971 Bomb, pg. 54). To see the inside of the dedication program, click here.

The Center's Mission

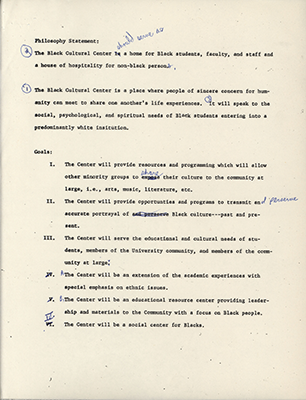

The Black Cultural Center devoted considerable effort to defining and refining its mission early on. In addition to a detailed mission statement (an early draft of which can be seen here, with handwritten corrections), the center also kept statistics on multiple facets and outcomes of all of its programs and offerings. To see the full draft of the mission statement, click here.

Mr. and Mrs. Hawkins: ISU Employees and Diversity Champions

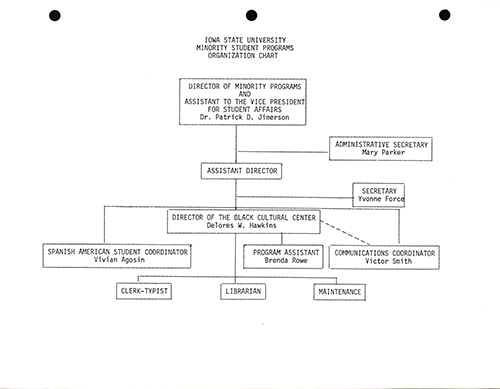

DeLores's career eventually took her to Des Moines Community College, where she worked as the Director of Financial Aid for many years. But one of her early positions at ISU, post-graduation, was that of Director of the Black Cultural Center in an interim capacity. Vern, on the other hand, worked for the admissions office, recruiting students from underrepresented backgrounds.

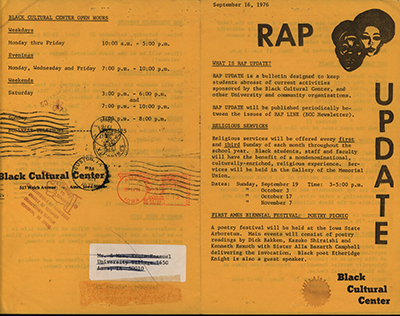

News/Activities Bulletins

The BCC's archival records contain multiple different news bulletins that were distributed at various points throughout the center's early years. Some of these overlapped in time, but seemed to serve different purposes. Others bore similar titles, for example RAPlineand the RAP Update, which could indicate variations of the same publication. The example featured here was printed as a simple, bulletin-style booklet and contained both event calendars and notifications regarding opportunities available in the surrounding area.

Home Away From Home

One goal of the cultural center was to provide a "home away from home" for black students at ISU: a safe place where they could both escape the constant pressure surrounding their day-to-day existence on a majority-white campus and also have fun socializing with friends. The center organized a number of activities, including picnics, baseball games, horseback riding, dances, and so forth. Black students have led rich and creative social lives as long as they have been on campus; however, these photographs constitute one of the first systematic attempts made by the school to document and preserve the memory of these social lives.

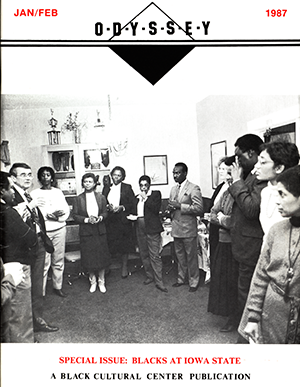

Role Models

The Odyssey is another newsletter published by the Black Cultural Center. It is unclear how long it ran, as current archival holdings contain only two editions. But this special edition from 1987 is particularly useful from a historical standpoint as a compendium of highly successful black faculty and staff working at the university at that point. Doubtlessly, it also served to inspire students of the time and strengthen the ties of the community.

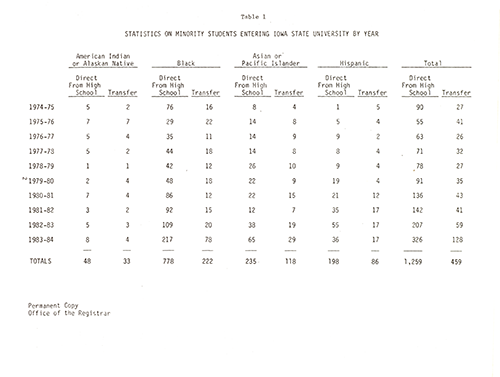

Results

Yet another benefit that the Black Cultural Center (and later its umbrella department, Multicultural Student Affairs) provided for ISU involved its first systematically-collected data on enrollment and retention of students from underrepresented groups. In part, these statistics served to justify the continued existence of the centers, but they also demonstrated that the services these centers offered played a substantial role in bettering students’ lives on campus, which increased their success.

Women and LGBTQ+

Rules, Regulations, and Gender Discriminatory Policies

DeLores began her studies at a point in ISU history that proved critical for women’s rights on campus, as well. Female students of the time were still living under strict rules and regulations which differed substantially from those their male peers were expected to follow. Shortly before DeLores arrived on campus, student government, under the short-lived auspices of Don Smith and Mary Lou Lifka, had begun to challenge these regulations. However, the first student handbook to make no differentiation between rules for men and women students would not appear until 1971. For most of DeLores’s college career, she would have been required to file a letter of approval from her parents prior to leaving Ames, adhere to a midnight curfew, and abide by her residence hall or household’s restrictions on when and where she would be permitted to entertain men6.

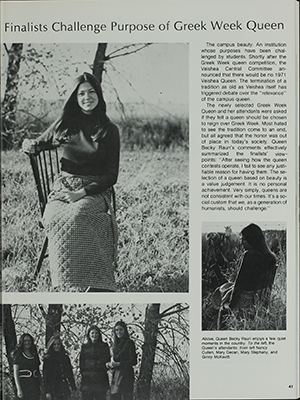

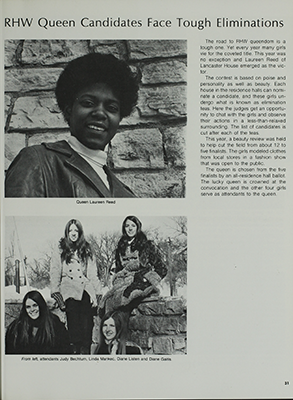

Challenging the Purpose of Greek Week "Queen"

The challenges that women students at ISU faced when DeLores was an undergraduate went deeper than policy, however, and often lived in the heart of beloved school traditions, the attitudes behind which had never been questioned or called out. The biggest change on this front that DeLores would have witnessed during her time as a student dealt with the school’s unexamined habit of appointing beauty “queens” on every occasion, whose Instagram-worthy portraits would then feature prominently in each yearbook. Doubtlessly, these and other well-documented school competitions which casually objectified women, had been on the minds of female students for a while. But not until 1972 (corresponding with the U.S. Congressional approval and Iowa ratification of the later-revoked Equal Rights Amendment), did students publicly challenge them (1972 Bomb, pg. 41).

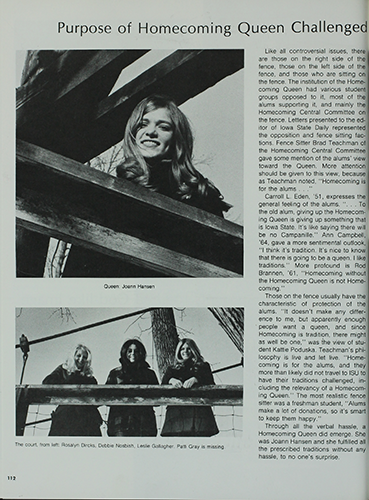

Challenging the Purpose of Homecoming "Queen"

The challenge to the Homecoming “Queen” tradition seems to have sparked the loudest controversy. Iowa State Daily printed opinions voiced from both sides of the argument, and the yearbook documented these debates over multiple pages. The wording with which the 1972 yearbook recounts the controversy, however, poses some interesting questions about implicit bias in the authorship, as the ultimately-elected “queen” is twice described as a woman who sensibly incited no such “hassle” (1972 Bomb, pg. 112).

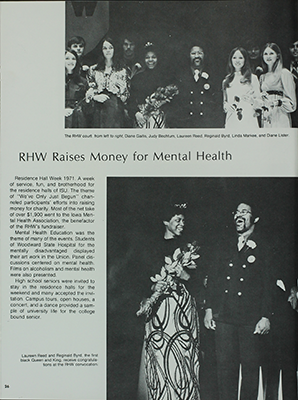

Electing the First Black "Queen"

Curiously, 1972 also marked the first year that any of the beauty pageants on campus elected a black “queen”, suggesting that at least a few proponents of the tradition, as well as critics, had begun to approach the practice with greater mindfulness about its underlying message and the statement it made about ISU cultural values. The newly-crowned Residence Hall Week “Queen,” Lauren Reed, also joined the first-ever black Residence Hall Week “King,” Reginald Byrd, in ensuring that the event raised sufficient funds for the mental health education causes they were supporting (1972 Bomb, pgs. 31 & 26).

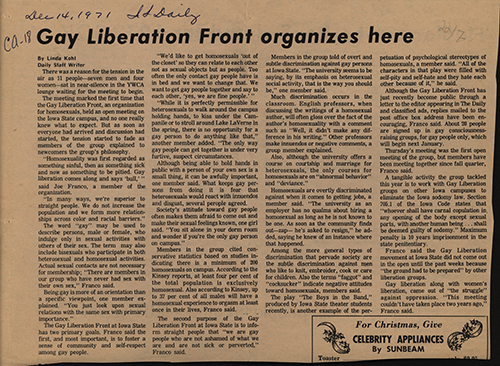

LGBTQ+ Activism

LGBTQ+ activism would not really take off on campus until after Vern and DeLores’s undergraduate years, as same-sex relationships were illegal in the state of Iowa until 1978, which meant that advocates could only come forward at great personal risk. Nevertheless, Iowa State Daily articles, and occasionally letters to the editor, point to the existence of activism on campus as early as 1971. Vern and DeLores, while not members of the LGBT community themselves, would have witnessed the burgeoning of this activism early in their ISU employment.

Vietnam War Protests

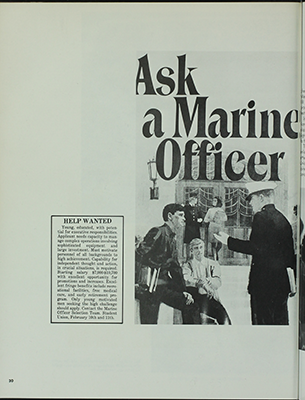

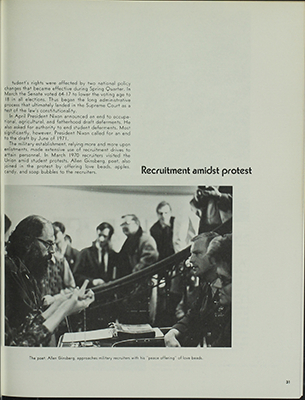

Recruitment and Selective Services on Campus

Nixon's 1969 amendment to the 1948 Selective Services Act (also known as the Elston Act) raised ire in students across the nation. While the draft age had already been expanded from 19-26 to 18-35 in 1967, students had been exempted until they completed their four-year degrees (or reached the age of 24, whichever came first). This changed with the 1969 amendment, however, which turned the draft into a randomized lottery from which only divinity students and young men with physical disabilities were excused. Ironically, while outraged ISU students held sit-in protests at the local selective services office, the military continued to recruit on campus. Even notable Beat Generation poet Allen Ginsberg visited campus one day and highlighted the discrepancy (1971 Bomb pgs. 30-31).

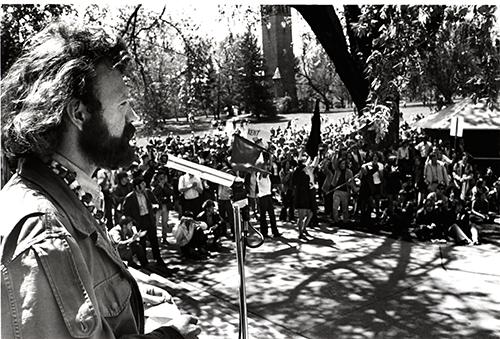

Campus Rally after the Kent State Shooting

In spite of loud discontent over recent alterations of selective services laws, anti-Vietnam War protests didn’t fully lift off the ground at ISU until the aftermath of the Kent State shootings in Ohio on May 4, 1970. The Government of the Student Body called for a 24-hour, full-campus strike, which was to begin at noon on May 6th. Over 3,000 students rallied on the Central Campus lawns in a show of support for the Kent State students, who had been gunned down by law enforcement on their own campus while protesting the Cambodian invasion (1971 Bomb pgs. 44-45).

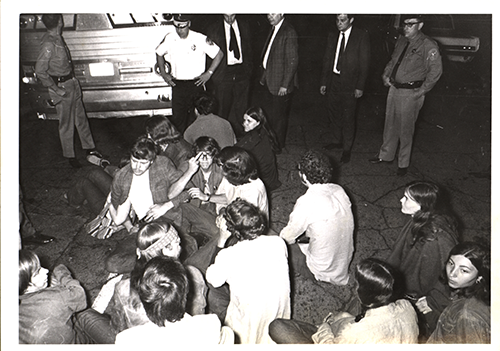

Lincoln Way Sit-In

Particularly disgruntled students expanded the May 6th sit-in to the middle of Lincoln Way in Campustown, blocking traffic and refusing to move.

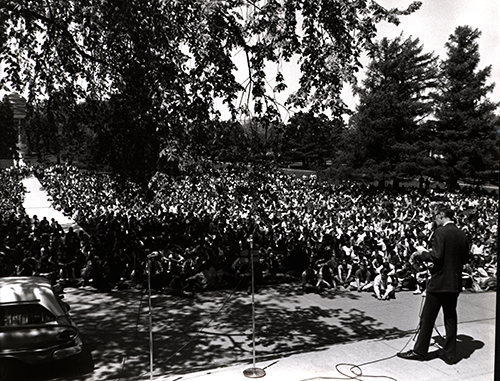

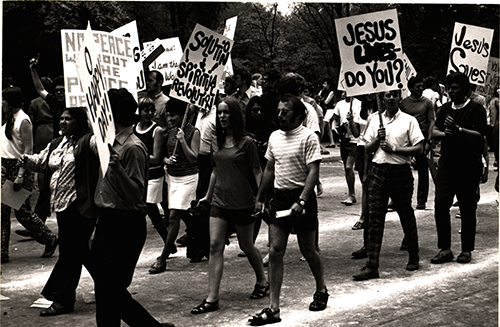

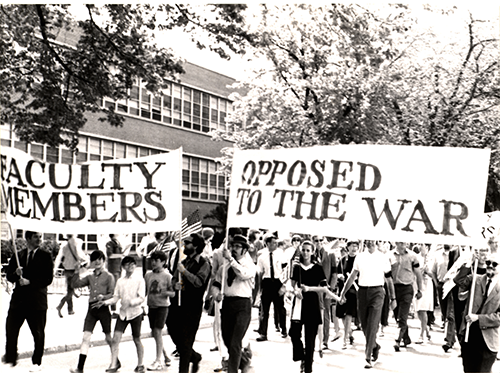

"March of Concern" at the VEISHEA Parade

Mere days later, anti-war sentiment took to the streets. More than 2,000 protesters followed the annual VEISHEA parade with a mile-long “March of Concern.” Photographs of the event show groups from all corners of campus, including religious organizations like the Campus Crusade (now known as Cru) as well as faculty and staff, uniting over the issue. The march ended on Central Campus, where President Parks addressed the crowd. That year, VEISHEA concluded with a re-lighting of the torch for peace “not just for the nation, but for campus”7. It is unclear whether this sentiment was sincere or should be interpreted as a passive aggressive form of tone-policing, but incidents immediately following the march suggest that a portion of the student body remained unsatisfied with these University-sanctioned gestures toward closure.

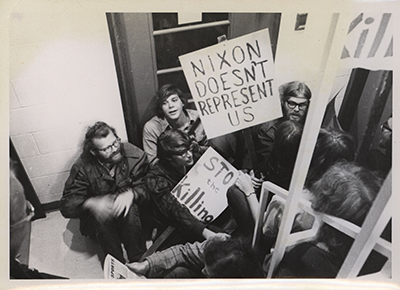

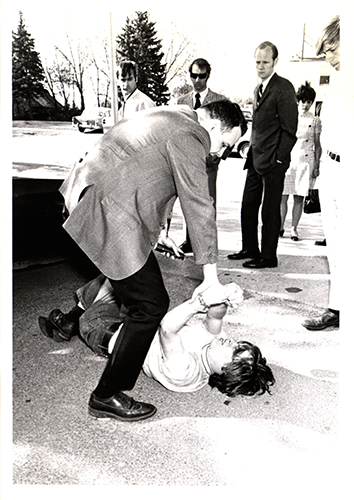

Law Enforcement Response

As protests became more disruptive, law enforcement began to intervene with increasing aggression. On Friday, May 8th, 1970, following the VEISHEA March of Concern, 22 students were arrested for a sit-in at the local selective services office, which clogged the stairwells and prevented individuals who worked there from leaving. A few weeks later, on May 22, 1970, a bomb exploded in Ames City Hall. The incident was not explicitly linked to student protests, but timing suggests a connection, and it is understandable that community members had grown concerned.

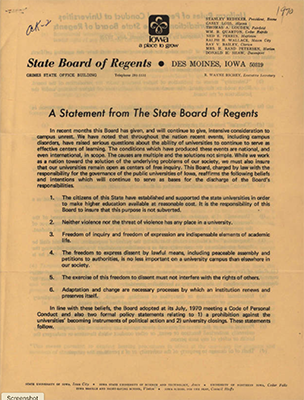

Board of Regents Response

In response to a perceived tendency toward violence in student protests, the Board of Regents released a statement explaining a decision to require all incoming freshmen to sign a code of conduct, which would, essentially, prohibit them from participating in non-sanctioned forms of protest. While there have been modifications over the years, it seems likely that the thought process behind this enforcement birthed many current policies surrounding acceptable use of the free-speech zone and the organization of “Non-Commercial Expressive Activities” on campus8.

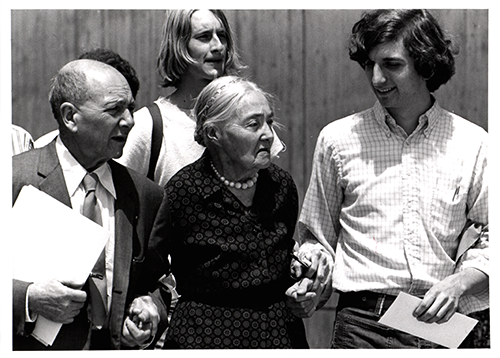

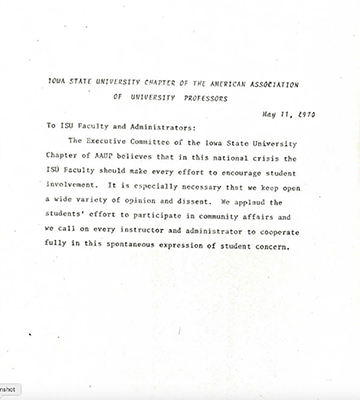

Faculty Response

In contrast, the ISU chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) resoundingly condemned the Board of Regents’ reaction in favor of championing students’ freedom of expression. It is likely that this attitude arose partly from some of the faculty’s own support of anti-war causes. Faculty and staff can be seen marching en masse in the VEISHEA March of Concern, but more readily identifiable shots of faculty members attending protests can also be found. An example is the photograph to the left, featuring the Math Department’s Edward S. Allen and Mrs. Allen.